There are cities you fall in love with at the first sight. There are cities leaving a very contradictory impression on you, and you do need a long time to recover from visiting them. That kind of revelation we made while travelling to the most controversial city in Europe, a ghetto city, a city of murals divided by concrete walls, and a capital of Northern Ireland – Belfast.

Belfast appears to have two guises: only you can choose whether you would like to see them both or would prefer to know either.

To feel the spirit of the city let us get a little insight into its history. The story dates back to the Middle Ages when Ireland became dependent on the British Empire. Since that time the Irish had been feeling quite strong pressure from their English neighbours who seized their land and oppressed the Irish language. Those events gave rise to continuous conflicts between the parties.

In 1801, Ireland officially became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; however that event only aggravated political tensions in Ireland. In 1913, IRA (Irish Republican Army),the first nationalist organisation,was established in Ireland. IRA members initiated rebellions over subsequent seven years, and in 1919 achieved the proclamation of the Republic of Ireland.

As a result of subsequent events on the island, Ireland (except for its northern part) withdrew from the Kingdom of Great Britain and became a separate state. Since the north of the island was inhabited mostly by natives of England and Scotland, who were loyal to the British crown, it remained part of the Kingdom and was doing quite well until the mid-sixties.

Over that period, Protestants, representing a majority in the Parliament, implemented a policy of discrimination against Catholics, who made up a third of local inhabitants. This was especially true in employment and housing opportunities. For example, Catholics could not hold public offices and were limited in choosing a place to buy a home.

A peaceful protest initiated by Catholics in the city of Derry to defend their interests appeared to be an apogee of the conflict and gave rise to a civil war. During that protest on 30 January 1972, British troops shot dead 13 unarmed civilians in Bogside, an inner suburb of Derry. Among them, the six were minors and one was a priest. Five of those were shot in the back. Those events are known as Bloody Sunday and stirred up a wave of strong disorders throughout Northern Ireland between the IRA and the British Armed Forces. Only 26 years after this horrible event, the official investigation came to the conclusion: the military had no legal ground to open fire on unarmed demonstrators.

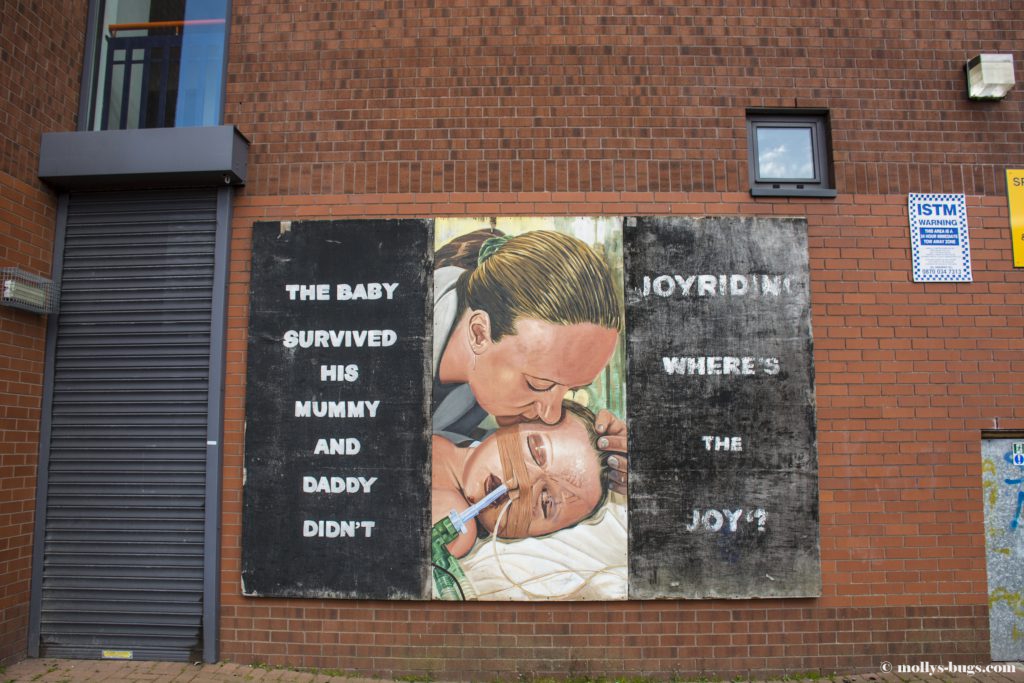

This was a point of no return for Northern Ireland to preserve fragile peace. Subsequent years demonstrated that the conflict between the two opposing forces was ever heating up, and the tension is well reflected in city murals which are very common in Belfast and Derry. At the height of the conflict, so-called “peace walls” were built in Belfast and Derry to separate Protestant and Catholic communities in the cities.

Notably, the last wall was built as recently as 2008. This is another confirmation that the incident is not over today, and there is a persistent threat to the conflict. That was what we exactly felt when went out to explore for famous Belfast murals. When you are in Belfast and would like to know more about its murals and their history, you can rent out a special black cab whose driver will be also your guide. He will drive you from one mural to another,so you could hear what historical events they depict. Interesting to know, the Irish themselves call their ethno-national conflict with a very capacious English word ‘The Troubles’ (even a dictionary defines this word as unrests in Ulster, clashes between workers). We preferred to explore the murals on our own, especially when you can easily find exact coordinates of most wall paintings on the web.

We did feel absolutely unsafe when we visited some Belfast areas. It was very untypical for Western European cities. Moreover, we were strongly recommended not to walk aroundBelfast Catholic communities at night. Besides, when you are in Belfast, be ready to see barbed wire almost everywhere – it shelters almost all fences and yards. All these observations did make us feel very anxious. In some Protestant communities, we saw grated windows on the first floor demonstrating the bursting nature of the Irish: one day a Molotov cocktail may be thrown to your home.

The city districts are divided by Protestant or loyalist communities (those who support the Crown) and Catholic communities (nationalists and IRA supporters). Protestant communities appear to be calmer, and we felt quite comfortable there unlike visiting Catholic communities.

The famous Shankill Road is the main Protestant street. It is relatively close to the centre and features a lot of fascinating murals.

If you ever get lost and cease to understand which community you are in, look at the flag to identify the political and religious mood of locals. The British flag and the flag of Ulster will suggest that you are in a Protestant community, while the Irish flag shows you are in the territory of nationalists and Catholics.

As I mentioned before, communities are divided by so-called “peace lines”, which are essentially concrete walls of different heights (it all depends on how aggressive the local residents are). In the past, there were even checkpoints protected by the military. There are about 20 walls in Belfast. Some of them look extremely unfriendly and are framed by observation towers more than 15 meters high. Today, Belfast walls appear not to play such an important role as they used to. Moreover, the guarded checkpoints are no longer operated. Nevertheless, locals strongly oppose against demolishing of these walls, as the lines make them feel safer.

While visiting Catholic communities, you do feel the strong and independent spirit of the Irish. A call to vote for the nationalist party Sinn Féin is seen at every corner. This party is believed to have a close connection with IRA known for its numerous terrorist attacks, such as an attempt to kill Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcheroran attack on MI6 with a rocket launcher. Belfast Catholic communities appear to be very respectful to all sorts of “friendly countries” facing a similar political situation. For example, there are murals immortalizing Cuban leader Ernesto Che Guevara or militants of ETA (Basque separatist organisation in the north of Spain).

The situation in the country is very ambiguous, and we do not undertake to judge what is happening there, but one thing is for sure – the conflict is not far from being over, and the current situation faced by the city is well described by one of its murals: “Prepared for peace, ready for war”.

You may also like:

All You Need to Know Before Traveling to Ireland

A City of Pubs, a City of Bridges, and a City of Colourful Doors: That’s All about Dublin

The Capital of Northern Ireland

P McMullan

Not all catholic communities are IRA supporters as per mentioned in your article. I see no mention of loyalist

paramilitaries such as the UVF when mentioning protestant communities. Please correct. Thank you

Mollysbugs

Thank you for your comment. I will correct it