Have you ever looked at a photo or some other image of a place and felt like you must visit it? It’s like an impulse or a physical necessity to be there. That’s how I felt when I saw a picture of Mount Fuji while browsing an atlas with my daughter. A strong need to go there. I’ve never felt like that before. Guess that’s what they mean by a call of the heart. Basically, ascending the high and sacred Mount Fuji was the prime motivator for our visit to Japan.

- Fujiyama or Fuji

- Picking the Time of Year

- Mountain Trails

- Picking the Time of Day

- Picking the Equipment

- Our Experience with Fuji

Fujiyama or Fuji

In the post-soviet space, the mountain is often called incorrectly, mainly due to a Soviet habit. Even such “competent” sources as Wikipedia still use the name Fujiyama, where “Fuji” is the name, while “yama” means “mountain”. But that is not correct. The Japanese never refer to it as “yama”, because it’s not a mountain, but a holy symbol to them. It should be instead referred to as Fuji or Fuji-san, where “san” means “sacred”, so it’s “sacred Fuji”. In English, the name is spelt with a J, but the correct pronunciation is “Fudzi”, with a “dzi” sound. But you’ll still be understood if you say Fuji.

Picking the Time of Year

Pictures and drawings almost always show Fuji with a nice symmetrical cone of snow on top. The mountain is snow-capped for about nine months a year, and scaling it during this time is impossible. The season for conquering the volcano fully depends on the snow. You must plan your ascent for a very specific period from the 1st of July until the 10th of September. So, there are only 70 days during which you can climb the mountain.

Mountain Trails

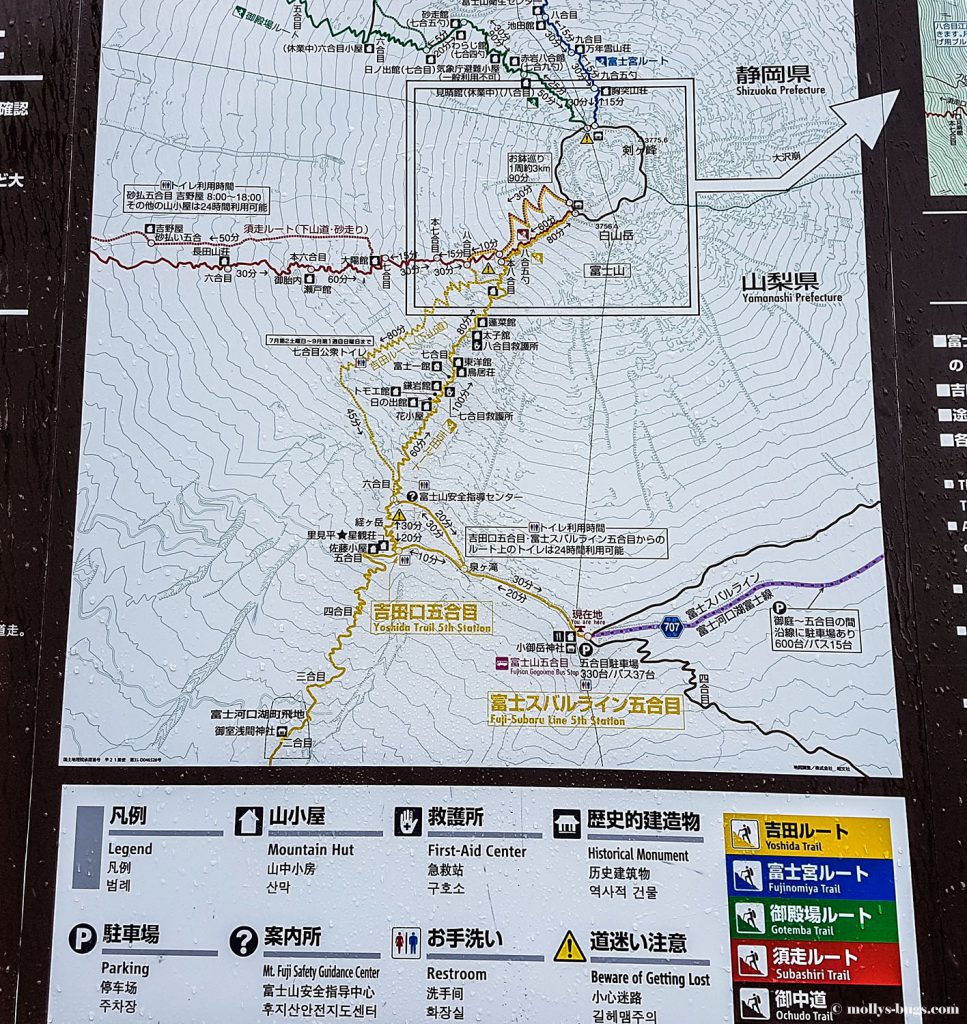

There are 4 routes you can take to the top. They vary by length and complexity and are distinguished by colour (yellow, green, red, and blue). An additional, black trail runs around the crater of Fuji at the very top.

We picked the yellow Yoshida path, the longest and most challenging trail. It starts at the fifth station, Fuji Subaru, and runs for 6 kilometres to the peak. Other trails are shorter and, judging by the descriptions, easier. But we wanted to fully experience the mountain, so we took the yellow path without hesitation.

Picking the Time of Day

The approximate time of the ascent was 385 minutes, so about 7 hours. That’s how long it takes to overcome the 6-kilometre distance. But this turned out to be a somewhat inaccurate calculation. You see, about 400 thousand people want to climb the mountain during the very short season. Divide this number by the 70 days when the ascent is allowed, and you get 5,714 people per day. In other words, almost 6,000 people on average take the four trails to the summit. That makes 1,500 people per route every day. These numbers mean only one thing: there are tons of people on the path, which makes the ascent very slow. There can even be jams that make the movement significantly slower. So, it’s physically impossible to get to the peak of Mount Fuji by the Yoshida trail in seven hours.

Picking the Equipment

Mount Fuji is 3,776 metres high, which is often misleading for those wishing to scale it. Don’t judge a mountain only by its height, as I did with Ben Nevis. Always be ready for heavy weather and don’t hope for the best in the mountains. Be ready for anything during your ascent. Especially when dealing with a dormant volcano. So, we tried to make our list of equipment as complete as possible, considering the temperature at the summit, the season, and the precipitation level. It included the following:

– Mountain boots that secure the shin. They’re necessary for any ascent since legs need protection more than anything else during hikes. Don’t forget that the trip is over if you twist your ankle. We saw many people climbing Fuji in sneakers, but it’s hard to imagine the state of their legs after 20 hours in the rain. At best, the sneakers will look like a rug. At worst, it’s a sure way to get an injury. The rain makes the rocks and the lava very slippery, but mountain footwear “clings” to them very well.

– Trekking poles. Sure, they’re not necessary, but the additional support will make things easier and will help you feel more confident as you go up.

– A raincoat or waterproof clothing. The cheapest option is a simple polyethene raincoat that can be worn over everything else. However, there will be a greenhouse effect that will make you sweat more. If you’re planning on trekking in the future, it’s best to purchase a good membrane jacket with a waterproof rating of 20,000 mm.

– Thermal underwear and a fleece jacket. Thermal underwear won’t provide any additional warmth, but it will immediately avert the sweat from your body. That way you won’t get sweaty and freeze. A fleece jacket, on the other hand, will keep you warm.

– A light winter coat. You can put it on immediately at the start of the climb or closer to the top depending on the temperature.

– An energy bar high in carbs, and water (1.5–2 litres per person). On your way you will see lodges that sell food, snacks, and hot beverages, but, firstly, they will be overpriced, and, secondly, you might need to snack before you get to one of them. Considering the number of people, the movement can sometimes come to a halt, so make sure to have a snack on hand to refill your energy.

– A headlamp is necessary if you’re scaling the mountain at night.

Our Experience with Fuji

Our ascent started at 11 am from the fifth station, Fuji Subaru, where we paid a fee of 1000 yen per person. It is paid by everyone, be it a tourist or a native. We planned our route while considering a few hours of rest in a lodge at station seven. By our estimations, we should have been there by 4 pm, but we only got there at 6 pm because of the jams. Fuji met us with thick mist and heavy rain, which at first made the climb seem impossible. During our trip, the rain periodically grew lighter or heavier, but it never stopped completely.

Don’t hope for a moment of solitude with the mountain, since the number of climbers is always huge. The Japanese looked at us with surprise, not getting why we would want to scale their sacred mountain. The boldest of them even came up and asked us this question in broken English. We’ve seen other foreigners on the route, but most of the climbers were Japanese. For them, ascending the mountain is like a ritual that they try to adhere to regularly. We’ve met a girl along the way that told us that she tries to scale the mountain every year, taking a different route each time.

We were very tired by the time we got to the lodge, and we planned to spend a few hours there before continuing the ascent at night. The cost of resting at these lodges depends on the distance to the peak. The closer it is, the higher the prices. A rest at the highest, ninth station costs 6,500–7,000 yen per person. There is also a time limit: no matter when you come, you must leave by 4 am. You get a sleeping bag and a modest dinner that can hardly cover your calorie needs.

You’re lucky if you can sleep in any conditions. I couldn’t even get a nap. People were constantly walking around, coming and going, always creating noise. The only thing I did manage to get is warmth. The Mormot sleeping bags they gave us were very warm. I got into mine while wearing my woollen thermal underwear and was completely warmed up in 40–50 minutes. In three hours we continued our ascent to get to the peak by 4 am and see the dawn.

A headlamp is necessary at night to light the path in complete darkness. Even though there were many people walking alongside us with flashlights, they weren’t enough to keep the ground under our feet visible without our own lamps.

There are no toilets or lodges between station nine and the peak. The map showed another station, marked as “9.5”, but when we got to it we saw that it was completely covered in soil and lava. Apparently, an avalanche came down and buried this place. So, during this portion of the way count only on your own food and water.

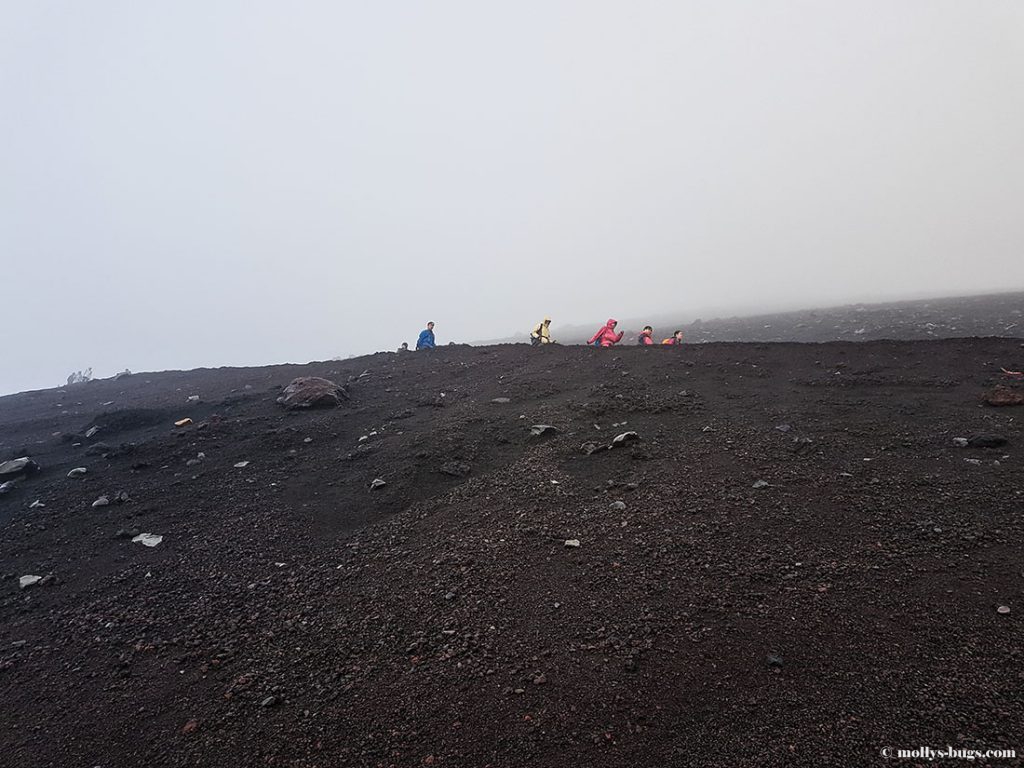

Near the very peak, around 300–400 metres before it, people’s behaviour starts to change. Some almost give up and sit down on the rocks, unable to get up and walk on, while others gather what strength they have left and rush to the top, pushing through the crowd to see the precious sunrise. The movement gets more chaotic near the peak and almost stops because of this. Be ready to stand there for a while. Don’t get nervous and don’t give in to the chaos caused by others.

500 metres before the peak (around 1.5 hours of walking) my thoughts randomly went back and forth from “I’m going to make it” to “I’m not going to make it.” Lack of sleep and food, the wind, the rain, and cold weather urged me to give up. In moments like this, it’s important to stop, look around, and realize that this is no time to lose heart. When you’re this close to the peak, you must go on! The turning point for me was when I saw a Japanese man sitting on a rock with hands uncontrollably shaking from the cold and the strain. He looked around with agitation and couldn’t do anything about his hands, while others moved along, not paying him any attention. This is when I realised that I didn’t want to be like him, to be the object of sympathetic looks, but to be at the peak, among those who made it. There were many people like that man on the way: around 10% of people don’t complete the ascent. It’s when I saw that man that my autopilot turned on and pushed me to go beyond my limits and get to the top.

As I reached the summit of Mount Fuji, I couldn’t hold back tears of joy because we made it, we didn’t break and, most importantly, we could overcome ourselves. We did it!

Even though we couldn’t see the sunrise through thick clouds, I was still grateful to the mountain for giving us the strength to get to the top safe and sound.

There is a café at the peak where you can get some hot food and rest from the emotions surging after the challenging ascent.

Our overall physical condition prevented us from taking the black trail to circle around Fuji’s crater. In an hour we started our descent via another route. It took us around 4–5 hours, and that path looked much easier than the one we took to scale the mountain. Its only drawbacks are gravy and volcanic sand that treacherously slide under the feet, posing a risk of slipping, gliding down, and spraining a leg. Be careful even as you go down. Remember that getting to the top is only half the way.

We barely made any stops on our way down and in 4–5 hours reached station five, the starting point of our ascent. The total time of ascent and descent was 22 hours including our rest at the lodge, which is not a bad result for a trail of that difficulty and the weather conditions. Even though it was raining the whole time, we didn’t get wet thanks to our equipment. Overall, our ascent of Mount Fuji can be considered a success. Sitting now in comfort, I am very glad that I had the willpower to push forward at the critical moment. That’s how life is: if you want to achieve something, you must work for it.

If you ever climb Mount Fuji, you might find yourself in different circumstances or pick a different route. Many people choose a shorter and easier trail, but as I said, we wanted to get the most from the mountain, and we sure did.

I hope that you’ll find our experience useful and interesting. And remember: the mountains are not for the weak!

Leave a Reply